Earlier this week Siddharth Chatterjee, Head of Strategic Partnerships at the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, called for all sides to lay aside political considerations in the fight against the recent outbreak of polio in Syria. “When it comes to children’s health,” Chatterjee said, “you have to get the politics out of the way.”

It doesn’t sound like anyone’s listening. “The virus originates in Pakistan and has been brought to Syria by the jihadists who come from Pakistan”, the Syrian Minister of Social Affairs told reporters. The government has said it will vaccinate every child in Syria, including those in rebel-held areas, without explaining how this would be achieved or responding to international calls for a humanitarian ceasefire. Syrian activists, meanwhile, accused the government of blocking supplies of aid and medical equipment to rebel-held areas.

It doesn’t sound like anyone’s listening. “The virus originates in Pakistan and has been brought to Syria by the jihadists who come from Pakistan”, the Syrian Minister of Social Affairs told reporters. The government has said it will vaccinate every child in Syria, including those in rebel-held areas, without explaining how this would be achieved or responding to international calls for a humanitarian ceasefire. Syrian activists, meanwhile, accused the government of blocking supplies of aid and medical equipment to rebel-held areas.

The imposition of politics on public health is nothing new. I’ve often been struck by the parallels between the Syrian and Spanish civil wars, and this story suggests obvious similarities to issues of war, health and politics under the Franco regime. Sadly, such parallels don’t suggest that Siddharth Chatterjee’s wish is going to come true any time soon.

As in the current conflict, disease was used for propaganda purposes both during and after the Civil War. Franco’s Director General of Health, José Palanca, claimed that spotted fever hadn’t occurred in Francoist areas before contact with enemy lines. The Civil War preceded the first European polio pandemics, but when the disease emerged in Spain in the early 1940s the regime initially refused to admit that an outbreak had taken place until it realised that it could use the association between polio and improved infant sanitary conditions to present it as a consequence of Spain’s economic and social development. On the opposing side, Republican authorities tried to restrict the activities of neutral international organisations such as Save the Children International for fear they’d be used as cover for the entry of nationalist spies.

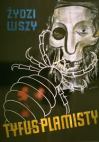

Of course, this link between war, disease and politics goes a lot wider than the Spanish Civil War. Nazi Germany was obsessed with the wartime risk of a typhus outbreak spreading from Eastern Europe and put considerable effort into disinfection and quarantine programmes. Typhus, however, was seen in Germany at the time as a Jewish disease, and infection control was ultimately used as a metaphor, justification and a practical model for the mass murder of Jews.

In wartime, it seems, health and politics are difficult things to separate.

Today’s Work Capability Assessments (WCA) were brought in under the last Labour government and have been extended under the coalition, and have come under widespread attack from the

Today’s Work Capability Assessments (WCA) were brought in under the last Labour government and have been extended under the coalition, and have come under widespread attack from the